Small Clues Series Introduction

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, social media has transformed into more than just a place for sharing opinions—it’s become a key front in the fight for truth and democracy. One particularly interesting development is NAFO (the North Atlantic Fellas Organization), a grassroots community dedicated to countering Russian propaganda online and promoting democratic values. High-profile leaders like Ben Wallace, Kaja Kallas, and Mark have publicly supported NAFO, giving political legitimacy to this digital pushback against the Kremlin’s disinformation campaigns. Yet, unexpectedly, influential figures such as US Senator Mike Lee and tech entrepreneur David Sacks have openly criticized NAFO, often repeating claims that closely echo official Russian talking points.

This raises an important question: How is it that these narratives align so closely with state-sponsored Russian propaganda, intentionally or otherwise? To shed light on this issue, we’ll examine how state-backed messaging infiltrates activist groups on the left and right, social media and podcasts, explore the Russo-Iranian media strategy, highlight specific websites involved in disseminating these ideas, and explain NAFO’s emergence as a grassroots response. By analyzing these digital networks, we’ll demonstrate how online narratives directly influence real-world political discussions and decisions. All the time we will refer to “small clues” – a tweet, a web page or a podcast can illuminate the online information war battle lines.

Understanding Temnik and its Strategic Application: A Case Study

We will explore the alignment of western activists with Russian disinformation narratives, their long-term ideological drift toward anti-Western foreign policy framing, and finally the broader context of how activism can be co-opted or re-framed. We will use information from PressTV emails obtained by Washington Outsider, the intelx.io platform and other open source intelligence (OSINT) tools to discover the connections from a seemingly credible left-wing activist organization.

The Russo-Iranian Media Axis and the White Helmets: A Case Study

We’ll examine how Russia and Iran coordinate disinformation strategies, and how these efforts manifest in high-profile campaigns—starting with the attempt to discredit Syria’s White Helmets. We will use information from PressTV emails, the intelx.io platform and other open source intelligence (osint) tools to discover how people who claim to be independent journalists use reflexive control for strategic purposes.

NAFO vs. the Disinformation Web: Key Websites and Communities

A deep dive into the grassroots resistance of NAFO and the online platforms—both overt and covert—that echo Kremlin-aligned narratives and attempt to shift policies to a more favorable platform for the Russian government.

Safeguarding Truth: Lessons and a Call to Action

We conclude with practical strategies for journalists, researchers, and citizens to detect, resist, and counter digital disinformation in the fight to protect open, fact-based discourse.

Ultimately, this series is a call to action for journalists, researchers, and the public alike—to be alert, question sources critically, and actively challenge disinformation. Protecting open, fact-based public discourse has never been more vital.

Understanding Temnik and its Strategic Application

Historical Context and the Art of Propaganda

For decades, the Russian government has honed a distinctive communication strategy—a blend of emotive language, selective fact presentation, and narrative framing designed to influence public opinion. This section explores the historical roots of these techniques, noting how similar rhetorical strategies to those used in State propaganda have emerged on social media platforms.

Language and Tone

Both spheres often rely on emotionally charged language and stark dichotomies (us vs. them), designed to simplify complex realities.

Narrative Framing

Just as government outlets might frame events to suit political ends, many social media messages tend to adopt similar narrative frames—sometimes emphasizing nationalistic or populist themes.

Echo Chambers and Viral Amplification

Social media’s algorithms can amplify messages that mirror familiar state narratives, reinforcing a cycle where controversial or polarizing content spreads rapidly.

Reflexive control is a strategic concept originating from Soviet and Russian military doctrine, referring to influencing an opponent’s decision-making by carefully shaping the information and perceptions available to them. Rather than overt coercion, reflexive control subtly guides targets toward decisions advantageous to the initiator. It exploits cognitive biases, moral frameworks, emotions, and pre-existing beliefs, causing individuals or groups to act voluntarily in ways aligned with the initiator’s strategic goals, often without awareness of manipulation.

[Reflexive control is a longstanding concept in Soviet and Russian military theory, see Gerasimov Doctrine and Thomas (2004) on psychological manipulation techniques.]

In practice, temnik functions as the delivery system, while reflexive control represents the strategic goal: shaping decision-making by manipulating the premises through which individuals or groups interpret information. When a domestic group, like LASG, adopts a worldview that aligns with authoritarian state messaging—without direct instruction—it demonstrates the subtle power of reflexive control. Through consistent narrative framing, actors become part of a broader messaging architecture, believing they’ve independently arrived at conclusions designed by others.

Temnik

“Temnik” (derived from the Russian/Ukrainian word for “theme” or “subject”) refers to informal but influential editorial directives or “theme instructions” that are disseminated—often from government or ruling-party circles—to media outlets. While the term originated in Ukraine during the early 2000s, it has become more widely recognized in the context of Russian media control and propaganda strategies. Since around 2008, when Russia’s information operations grew more sophisticated (particularly following the Russo-Georgian War), the concept of “Temnik” has taken on greater significance. Here are the key points:

- Centralized Messaging

o Definition and Purpose: Temniks are essentially “talking points” or “guidance documents” intended to unify the message across state-controlled and sympathetic private media. They often contain directives on how to frame news stories, which topics to prioritize or downplay, and which narratives to push.

o Top-Down Control: They reflect a top-down approach, where editorial freedom is curtailed by the need to adhere to officially sanctioned perspectives. - Evolution Since 2008

o Russo-Georgian War: The brief conflict in 2008 marked a turning point, showcasing the Kremlin’s evolving methods of information warfare. Temnik-style instructions ensured Russian media outlets presented a unified narrative that blamed Georgia for aggression and portrayed Russia as a peacekeeper.

o Institutionalization: Over time, the practice of distributing temniks became more formalized through state institutions, think tanks, and Kremlin-linked public relations firms, creating a more seamless alignment between political objectives and media output. - Integration with Digital Platforms

o Social Media Influence: As social media grew in importance, temnik-like guidelines expanded beyond traditional TV and print outlets. State-backed media and “troll farms” leveraged these directives to shape online discourse, amplify pro-Russian viewpoints, and discredit opponents.

o Adaptability and Flexibility: Modern temniks aren’t rigid—they’re flexible and tailored for different platforms (e.g., Twitter, Telegram, YouTube), ensuring consistent messaging across various audiences. - Strategic Objectives

o Narrative Control: By distributing cohesive talking points, the Russian government aims to present a monolithic viewpoint that crowds out dissenting voices. This control extends to foreign-language outlets like RT (formerly Russia Today) and Sputnik.

o Domestic and International Reach: While the primary target is the Russian-speaking domestic audience, temnik-style directives also shape how state-backed media outlets present stories to international audiences, influencing global perceptions of events such as the annexation of Crimea, the war in eastern Ukraine, and other geopolitical flashpoints. - Impact on Information Environment

o Marginalizing Opposition: Opposition figures are typically cast as foreign-influenced, extremist, or illegitimate, thereby undermining dissent and reinforcing the government’s legitimacy.

o Consolidation of Power: By ensuring near-universal media compliance, the Kremlin strengthens its ability to maintain control over the narrative, limit public debate, and promote policies with minimal pushback.

In this way, temnik serves as a delivery system for reflexive control: guiding decisions, reshaping perceptions, and ultimately provoking behaviours that align with the Russias strategic objectives, all while preserving the illusion of autonomy and moral clarity in the target audience.

Recognizing the presence and influence of temnik requires heightened vigilance, critical thinking, and systematic verification practices. Media literacy education, independent analysis, and active counter-narrative efforts are essential to neutralize temnik’s influence and maintain informational integrity.

Temnik – Controlling Western Media through co-operation between Iran and Russia

Temnik effectively exploits cognitive biases, existing beliefs, and moral frameworks within targeted groups, subtly steering their actions and decisions. It capitalises on the credibility and authority of established voices, thereby enhancing the perceived legitimacy of disseminated narratives.

The document attached here proposes the establishment of an English-language analytical news platform in collaboration with RT/Sputnik in Russia to counter what Iran perceives as dominant Western narratives and amplify Iran-aligned perspectives. Given Iran’s historical weakness in international media presence, the platform aims to provide a an “Iranian” voice in global discourse. Here is a summary of the document which has been translated for us by a native Farsi speaker. We will look again at this document later in the series, for now we will just use the summary to highlight alignments between online influence and the Russian and Iranian governments.

- Necessity of the Project:

o Western governments expand their media influence yearly, suppressing alternative voices.

o The internet has enabled opposition movements to challenge Western narratives, creating a need for Iran to do the same.

o Countries like Russia and Qatar have successfully funded alternative media outlets (RT, Middle East Eye), whereas Iran has struggled to create an impactful platform. - Implementation Scenarios:

o Independent Platform Outside Iran (Preferred Approach):

Avoids bias perception, making content more credible.

Easier collaboration with foreign experts.

However, it is costly and challenging to maintain.

o Platform Inside Iran:

Lower operational costs and easier administration.

However, it would struggle with credibility and international cooperation. - Proposed Strategy:

o Establish the platform in Lebanon, leveraging an experienced editorial team.

o Focus on news, analysis, investigative journalism, interviews, debates, and viral videos.

o Partner with RT and social media networks to amplify content.

o Challenge Western policies in the Middle East while engaging Western intellectuals. - Editorial Team:

o Composed of experienced journalists and analysts, including Sharmin Narwani, Hala Jaber, Elijah Magnier, and Dr. Amal Saad. - Budget Estimate:

o Annual cost: $514,000, covering editorial salaries, guest writers, graphic design, website maintenance, and video production. - Expected Impact:

o The platform would become a key media hub for the Resistance Axis.

o It would provide an independent, credible voice for Iran-aligned narratives in global media.

o Social media outreach and partnerships would maximize its influence.

Within the document there is a section which summarizes which current sites and platform support Iran and Russia and the amount of support they receive from the Kremlin.

“For example, Russia explicitly supports some websites financially and ideologically. Some prominent Russian-backed platforms include:

• South Front, The Duran, The Strategic Culture, New Eastern Outlook

Additionally, other websites that align with Kremlin policies, though their Russian funding has not been confirmed, include:

• Global Research, Voltaire Net, Off Guardian

There are also various opposition platforms, often associated with left-wing anti-war movements or the new progressive wave in the U.S., which strongly oppose American interventionist policies. Some of these include:

• CounterPunch, The UNZ, The Saker, Grayzone Project, Activist Post, Anti Media, TruthDig, Truthout, ConsortiumNews, WSWS, Sott, Information Clearing House, Dissident Voice, Zero Hedge, Anti War”

Let us take a look at the platforms discussed in the Iranian-Russian Media strategy which we will encounter in our analysis of the LASG information network.

SouthFront

• Political/Ideological Bias: SouthFront is a multilingual site with a strong pro-Russian, anti-Western bias, often promoting Kremlin-aligned narratives. Its content focuses on military conflicts and international affairs from a Russian perspective (South Front – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). Analysts note it “loyally relays whatever suits the Kremlin” while pretending to be independent (SouthFront – Wikipedia). Media watchdogs classify SouthFront as a conspiracy-driven outlet that secretly pushes Russian propaganda and frequently publishes misleading or false information (South Front – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check) (South Front – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check).

• Affiliations and Government Links: Evidence indicates SouthFront is controlled or influenced by the Russian state. It is registered in Russia (Crimea) and has been “accused of being an outlet for disinformation and propaganda under the control of the Russian government.” (SouthFront – Wikipedia) U.S. authorities have explicitly tied SouthFront to Russian intelligence: a 2022 U.S. Treasury report said SouthFront is owned or controlled by Russia’s FSB (security service) (SouthFront – Wikipedia). Accordingly, the U.S. Treasury sanctioned SouthFront as an arm of Russian state disinformation, and social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter) have banned its accounts for “coordinated inauthentic behavior” linked to Russia (SouthFront – Wikipedia) (SouthFront – Wikipedia).

• Funding and Transparency: SouthFront operates with no transparency about its ownership or funding. The site provides no list of owners or editors, and articles are published anonymously (South Front – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check) (South Front – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). Clues indicate a Russian origin: its web domain is registered in Russia, and donation links (via PayPal) use a Russian email/address, though the site does not openly admit its Russian base (South Front – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). SouthFront claims to be a volunteer-run, non-profit project, supported by reader donations, but investigators note it “goes to great lengths to hide its connections to Russian intelligence.” (SouthFront – Wikipedia) (South Front – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check) In short, its funding likely comes through opaque channels aligned with Russian interests (ostensibly “donations,” but facilitated out of Russia).

• State Influence and Expert Assessments: Multiple expert analyses label SouthFront as part of Russia’s state-backed influence campaigns. The EU’s disinformation task force (EUvsDisinfo) and independent researchers have repeatedly flagged SouthFront for spreading Kremlin propaganda in the guise of news (SouthFront – Wikipedia). For example, during Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, SouthFront echoed Moscow’s talking points (even calling the invasion a “peace enforcement operation” in one piece) (South Front – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). The site has a “Low” factual reliability rating from Media Bias/Fact Check, which calls it “a strong conspiracy site” and not credible due to its propagandistic content (South Front – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). Overall, SouthFront is widely viewed as a Russian government-affiliated disinformation outlet, advancing Kremlin geopolitical narratives under the veneer of an independent analytical website (SouthFront – Wikipedia) (SouthFront – Wikipedia).

Strategic Culture Foundation

• Political/Ideological Bias: The Strategic Culture Foundation (SCF) is a Moscow-based online journal that operates under the guise of a geopolitics think tank. In reality, it has a strong pro-Russian, anti-Western editorial stance. U.S. media and experts characterize SCF as a conservative, pro-Kremlin propaganda website that advances Russian state interests (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia). Its articles consistently criticize Western policies and NATO while defending or promoting Russian foreign policy objectives. To lend credibility, SCF often publishes pieces by Western fringe commentators or conspiracy theorists, effectively laundering Russian narratives through foreign voices (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia). This content strategy lets SCF push ideological biases (anti-U.S., anti-NATO sentiment) behind a façade of scholarly analysis. In short, SCF’s bias is heavily slanted toward Kremlin viewpoints, framing global events in line with Russia’s strategic narrative.

• State Sponsorship and Funding: Strategic Culture Foundation is widely assessed to be directed and funded by the Russian state. According to the U.S. State Department, SCF “is directed by Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) and closely affiliated with Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.” (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia) In other words, Russia’s intelligence apparatus guides SCF’s operations, making it an arm of official influence efforts. The site was founded in 2005 as a project of a Russian government-affiliated think tank, and Western authorities consider it essentially state-run. In 2021 the U.S. Treasury sanctioned SCF for its role in Russia’s interference in the 2020 U.S. election (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia). (SCF had published articles aimed at influencing U.S. voters.) Funding for SCF is not transparent in its publications, but investigative reports indicate it is financed through Kremlin channels – effectively a propaganda outlet underwritten by the Russian government (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia) (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia). The UK government and EU have similarly recognized SCF as part of Russia’s state media/influence network, with the UK imposing sanctions on some of its contributors in 2022 (Foreign Secretary announces sanctions on Putin’s propaganda) (Treasury sanctions Russian online outlets for spreading disinformation).

• Disinformation Activities: Strategic Culture is a key node in Russia’s disinformation ecosystem. It has a documented pattern of coordinating with other Kremlin-backed outlets: SCF shares articles with sites like Global Research, New Eastern Outlook, and SouthFront to amplify the same narratives (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia). Facebook identified and removed a network of fake accounts in 2020 that were operated by SCF to spread conspiracy theories targeting English-speaking audiences (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia). Those conspiracies included false claims that COVID-19 was a U.S.-created bioweapon and that vaccine efforts were a front for installing tracking microchips (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia). The Washington Post dubbed SCF “a phony think tank” after revealing how it spread lies about Bill Gates and pandemic vaccines (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia). In essence, SCF has been directly implicated in state-backed influence campaigns and online disinformation operations. Its content is not only biased but has often been objectively false or misleading as part of these campaigns. (For example, EU vs Disinfo detailed how SCF-run sites fabricate narratives while obscuring their Russian origin (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia).)

• Reputation and Expert Analysis: Media and intelligence assessments uniformly regard SCF as an untrustworthy propaganda outlet. The U.S. government explicitly calls it an “arm of Russian state interests” (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia). Independent researchers (e.g., the State Media Monitor project) categorize Strategic Culture Foundation as “State Controlled Media.” (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia) Media Bias/Fact Check also lists SCF as a Questionable source, citing its extreme bias, promotion of conspiracies, and lack of transparency intended to deceive readers (Chat Thread – Free Discussion – Page 139 — MI6 Community). In practice, SCF does not disclose its true backing and presents itself as a genuine think tank, which is misleading given its agenda. Overall, Strategic Culture Foundation is widely seen as a proxy of Russian foreign influence – a pseudo-think-tank used to legitimize and spread Kremlin propaganda internationally (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia) (Strategic Culture Foundation – Wikipedia).

Consortium News

• Bias/Ideology: Consortium News (est. 1995 by journalist Robert Parry) is an investigative news site with an anti-war, anti-interventionist orientation. Its bias leans left-of-center, often critical of U.S. foreign policy and the “establishment” (it has been likened to a Wikileaks-like outlet without leaked docs) (Consortium News – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). MBFC classifies it as Left Biased and mostly factual but heavy on opinion (Consortium News – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). Consortium News strongly opposes NATO expansion and U.S. military actions, sometimes to the extent of echoing Moscow’s perspective on events like the Ukraine conflict.

• Funding/Ownership: It is published by the nonprofit Consortium for Independent Journalism. The site relies on donations from readers and philanthropists (Consortium News – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). Some notable donors have been disclosed: Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters gave $25k in 2020 and 2021, and the Cloud Mountain Foundation (a U.S. progressive foundation) also contributed about $25k over the years (Consortium News – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). There’s no evidence of funding from any government – the support comes from private donors who share its skeptical view of Western militarism.

• Notable Assessments: Consortium News has drawn controversy for its Russia-related coverage. In 2022, the ratings firm NewsGuard issued a “red” reliability rating, citing “false or misleading information regarding Ukraine” on the site (Consortium News – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). (For example, CN has characterized the 2014 Ukraine revolution as a “coup” and echoed Russian talking points on the war.) The site vehemently denies publishing falsehoods and even filed a lawsuit in 2023 against NewsGuard and the U.S. government, accusing them of defamation and censorship for flagging its content (Consortium News – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). While no official body has proven Consortium News is part of a foreign disinformation campaign, its editorial line often dovetails with Russian narratives. Media bias analysts describe it as strongly anti-imperialist to the point that it sometimes uncritically relays claims from Moscow (e.g. doubts about chemical attacks or election meddling). In summary, Consortium News is a left-leaning, donor-funded outlet whose criticism of U.S. policy has led some watchdogs to label it as spreading Kremlin-friendly disinformation (Consortium News – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check), though it frames itself as simply “speaking truth to power.”

The Grayzone Project (The Grayzone)

• Bias/Ideology: The Grayzone is a far-left investigative site known for vehemently anti-US, anti-“Western imperialism” reporting. It often defends or downplays abuses by regimes opposed by the West. MBFC rates Grayzone “Far-Left Biased and Questionable” for its one-sided propaganda and conspiracy promotion (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check) (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). Its editor Max Blumenthal champions socialist and anti-imperialist viewpoints – e.g. Grayzone strongly supports Venezuela’s government and opposes U.S. sanctions/regime-change policies (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check), and it’s sharply critical of Israel’s policies (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check).

• Funding/Ownership: Founded in 2015 as a project of AlterNet and spun off in 2018 (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check) (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check), Grayzone is now owned by Max Blumenthal. It claims to be funded by reader donations (no advertising or big corporate sponsors) (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). Blumenthal himself has worked for Russian state media (he’s a regular on RT and Sputnik) (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check), but there’s no direct evidence that the site is financed by a foreign government.

• Notable Assessments: Grayzone’s reporting is widely criticised for aligning with authoritarian regimes’ narratives. It has, for instance, published claims denying chemical attacks in Syria (in line with the Assad regime’s position) (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check) and pushed unsubstantiated conspiracy theories (e.g. speculating that U.S. politician Pete Buttigieg is a CIA asset with no evidence (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check)). A Radio Free Asia report found The Grayzone is frequently cited by Chinese Communist Party media as a “launderer” of Beijing’s propaganda – Chinese state outlets cited Grayzone content 313 times in a little over a year (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). Grayzone writers also cast doubt on Uyghur human rights abuses and other issues in ways that echo Chinese and Russian official lines. In general, while it bills itself as “independent,” experts classify Grayzone as part of a “fringe media” network that amplifies Russian and Chinese disinformation (The Grayzone – Bias and Credibility – Media Bias/Fact Check). (No formal state ties are confirmed; rather, it’s an ideologically driven alliance of narratives.)

Temnik in Action – An evidence based breakdown – OSINT Platforms (IntelX.io)

The Los Alamos Study Group (LASG.ORG)

Background: LASG and Its Publications – A standard analysis

Here is a basic analysis and summary of the Los Alamos Study Group (LASG) carried out without an understanding of Temnik.

The Los Alamos Study Group (LASG) is a New Mexico–based nonprofit watchdog focused on nuclear weapons policy, environmental compliance, and disarmament. Since its founding in 1989, LASG has produced technical reports, legal filings (e.g. NEPA lawsuits), and budget analyses related to U.S. nuclear weapons complexes. While LASG is an advocacy organization, its detailed research on issues like plutonium pit production, lab safety, and nuclear budgets has occasionally entered the mainstream policy discourse. The key question is whether LASG’s reports have been formally recognized or cited by neutral, authoritative institutions – such as government agencies, think tanks, academics, or technical media – in shaping nuclear weapons policy or compliance decisions.

Citations in U.S. Government and Congressional Research

Congressional Research Service (CRS): Notably, the nonpartisan CRS has drawn on LASG expertise. In a 2014 CRS report to Congress on plutonium pit production, CRS analysts commissioned LASG’s executive director Greg Mello to contribute an analysis of alternatives. The report explicitly notes that Mello’s input “merits particular attention” given LASG’s history of National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) litigation on Los Alamos projects (sgp.fas.org) CRS even cited LASG’s online documentation of this litigation in a footnote (sgp.fas.org) ( sgp.fas.org.) In the acknowledgments, the CRS authors thanked “Greg Mello and Trish Williams-Mello of Los Alamos Study Group, for continuous assistance during the entire project, including discussions [and] responses to many requests for information” sgp.fas.org. This indicates a significant level of credibility and reliance, with CRS treating LASG as a knowledgeable resource on nuclear facility issues.

Government Accountability Office (GAO): The GAO has also formally engaged LASG. For example, in GAO’s 2013 review of NNSA’s plutonium strategy, the audit report states GAO consulted several nongovernmental organizations, “including the Los Alamos Study Group, the Union of Concerned Scientists, Nuclear Watch of New Mexico, and Project on Government Oversight,” to gather expert perspectives gao.gov. While the GAO report (GAO-13-533) doesn’t quote LASG publications directly, the inclusion of LASG in its methodology shows official recognition of LASG’s expertise as a stakeholder in nuclear enterprise issues.

Department of Energy / NNSA: DOE and NNSA documents typically cite official sources, but they have had to formally respond to LASG’s technical comments and legal challenges. LASG’s persistent NEPA lawsuits compelled NNSA to prepare additional environmental analyses for projects like the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement Nuclear Facility (CMRR-NF). A 2011 federal court decision notes that DOE announced a new Supplemental EIS partly in response to LASG’s lawsuit (which led the court to dismiss the case as moot) casetext.com Furthermore, in environmental impact statements, NNSA often acknowledges and addresses LASG’s public comments. For instance, the Final Supplement Analysis of the 2008 LANL Site-Wide EIS lists “Mello, Greg – Los Alamos Study Group” among the commenters energy.gov, and DOE’s responses to LASG’s technical critiques become part of the official record. While this is not a citation of LASG research per se, it is formal recognition of LASG’s role in informing environmental compliance.

Congressional and Executive References: Members of Congress and defense officials have sometimes referenced LASG’s findings indirectly. In one Pentagon-commissioned rebuttal of “minimum deterrence” proposals (released via the DOD FOIA reading room), the authors cite a 2015 LASG budget analysis. The report’s footnotes use LASG’s press release titled “Administration’s warhead design, production budget larger than Reagan and Bush – again” as a source for nuclear weapons spending figures esd.whs.mil. It’s noteworthy that the Department of Defense chose LASG’s data to illustrate budget trends, suggesting that LASG’s quantitative research on warhead budgets was seen as reliable enough to include alongside official sources in that context.

However, it should be noted that direct citations of LASG in primary government policy documents are relatively rare. Agencies like NNSA or DOE do not typically cite advocacy group reports in decision documents; at most, they acknowledge receiving input from LASG. The examples above (CRS, GAO, a Pentagon study) underscore that LASG’s work has been considered and sometimes integrated by government researchers or auditors, but this remains the exception rather than the rule.

Influence and Credibility in the Broader Expert Community

Considering the above evidence, LASG’s technical reports and legal efforts have achieved a measure of recognition among experts, though primarily in the watchdog and arms-control community rather than from proponents of nuclear expansion. LASG’s detailed analyses – on topics like plutonium pit lifetimes, storage capacity, budget overruns, and environmental risks – have been used by decision-makers and advisors when those insights align with policy scrutiny or reform efforts:

• Informing Policy and Decisions: LASG’s work has tangibly informed policy outcomes in a few cases. Their NEPA lawsuits, backed by technical arguments, forced the NNSA to revisit environmental analyses (e.g. preparing a new Site-Wide Environmental Impact Statement for Los Alamos in 2022, an action that groups like LASG and NRDC had long called for apnews.com). Although one cannot attribute multi-billion-dollar project decisions to a single NGO, the 2012 decision to defer the CMRR-NF construction was influenced by a combination of fiscal reality and watchdog pressure – LASG played a role by highlighting the project’s cost escalation and seismic safety issues in both legal and public forums. Additionally, LASG’s budget compilations have provided ammunition to members of Congress sceptical of nuclear spending. For example, when Senators questioned NNSA’s pit production plans by citing the existence of thousands of reserve pits and the century-long lifespan of plutonium cores, they were echoing points that LASG and allied scientists (like those cited by LASG) had circulated docs.pogo.org docs.pogo.org. Thus, while LASG is an outside voice, its data and arguments sometimes trickle up into congressional debates and agency decision-making processes.

• Credibility vs. Advocacy: Within the expert community, LASG is respected for its granular knowledge and integrity of data, but observers also know it has an advocacy stance (pro-disarmament). Sources like InfluenceWatch note LASG’s left-of-center, anti-nuclear orientation influencewatch.org, which can make more establishment-aligned analysts cautious about directly endorsing LASG conclusions. Major think tanks like RAND Corporation or the Carnegie Endowment typically do not cite LASG by name – instead they rely on government sources or their own analysis. This suggests that LASG’s direct influence in high-level policy studies is limited. However, the fact that CRS and GAO have engaged with LASG indicates that on specific technical matters LASG has credibility. Arms-control experts and NGOs widely regard LASG as a reliable repository of documents and analysis (for instance, LASG’s website hosts hard-to-find government reports, budget tables, and environmental impact statements, which experts access and cite). The Cato Institute’s open recognition of Greg Mello as an expert, alongside folks from Stimson and FAS, highlights that in nuclear policy circles LASG is considered part of the informed debate cato.org

• Extent of Influence: In summary, LASG’s publications have been formally cited in a variety of neutral or official contexts, from CRS reports to oversight studies and media reports. Such citations are usually to factual or analytical content LASG provided (e.g. budget figures, legal findings, technical critiques), rather than endorsements of LASG’s policy positions. The influence of those citations has been meaningful in reinforcing critiques of nuclear weapons programs. LASG’s data and arguments have bolstered the case for slowing or reconsidering projects like new pit production facilities docs.pogo.org docs.pogo.org, and for demanding stricter environmental reviews. Within the broader expert community, LASG enjoys a niche credibility: it is valued by arms control and environmental experts, frequently consulted by journalists, and occasionally acknowledged by government researchers. At the same time, it remains an advocacy group, so its reports are not mainstream policy references in the way official studies are.

Ok – so that is the traditional analysis of LASG.org – a left of center independent watchdog with a nuclear focus. Note that ai search engines were so convinced of the LASG expertise that they continually referred to Mello as being a government employee at Sandia or a qualified nuclear weapons expert. What is going on? What are we seeing here?

LASG – A drift towards Russia – How can an understanding of Temnik identify Russian propaganda

To concretely illustrate how temnik and reflexive control operate in practice, consider the case of the Los Alamos Study Group (LASG). Originally respected for rigorous oversight of U.S. nuclear facilities, LASG effectively leveraged technical analyses and legal mechanisms, notably contributing to the cancellation of the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement – Nuclear Facility (CMRR-NF) project. However, LASG’s narrative shifted significantly around 2014, coinciding with increased Russian geopolitical assertiveness.

Without overt control, LASG absorbed and amplified messages closely aligned with Russian strategic interests: depicting NATO expansion as the root cause of conflict, framing U.S. nuclear modernization as aggressive rather than defensive, and characterizing Western media coverage as inherently misleading. This alignment demonstrates the subtle effectiveness of temnik: LASG’s previously earned credibility became an instrument of legitimacy, enhancing the perceived authenticity of narratives supporting Russian reflexive control objectives.

Thus, LASG’s ideological transformation exemplifies how credible domestic actors can unwittingly become vectors in broader geopolitical narrative strategies, underscoring the potency of temnik in shaping perceptions.

Ukraine Temnik in action

Using search facilities provided by IntelX a number of strange quotes and sites appeared in the LASG data. Why would a group focused on Los Alamos have a “Ukraine News” page?

https://lasg.org/Ukraine/Ukraine.html

In bulletin 313:

“ We will be happy to host virtual discussions, not just about U.S. nuclear weapons but also about the hybrid war against Russia (“in Ukraine” doesn’t capture it, does it?). Again, if you are interested tell us when you CAN’T take part. We can bring in other experts as well if there is enough interest.”

Here we can see a definite support for Russia. LASG has never functioned as a traditional research organization in the academic or policy sense — i.e., peer-reviewed, methodologically neutral, or widely cited across ideological lines.

Let’s start to break down what has happened. Using a process of validation and fact checking the history of LASG we can start to build a picture of the shift from the local to the global in the LASG activism.

LASG History

What LASG has done:

• Produced factually accurate, granular analysis of U.S. nuclear programs (especially Los Alamos).

• Made useful primary source compilations (budgets, EIS documents, NNSA planning memos).

• Participated in litigation that influenced federal reviews, compelling EIS supplements or project delays.

• Been consulted by CRS and GAO as a stakeholder, not a neutral expert.

What LASG has not done:

• Published peer-reviewed, methodologically transparent studies.

• Been widely cited by mainstream research institutions (e.g., RAND, Carnegie, Brookings) for policy development.

• Provided balanced or multi-perspective analysis.

• Built a scholarly reputation separate from its advocacy identity.

How have LASG built their reputation as a credible source

Circular promotion operates through a tightly interconnected network of ideologically aligned websites, media outlets, and public figures. These entities consistently publish narratives that mutually reinforce one another, creating the appearance of broad consensus and widespread agreement. Because they frequently reference, quote, or cite each other’s publications, an illusion of legitimacy and authenticity is generated, even in the absence of independent verification or credible external evidence.

When mainstream institutions or media organizations reject or criticize these ideologically aligned sources, such rejection is strategically reinterpreted and portrayed as proof of their narratives’ validity. Claims of being silenced, censored, or suppressed by a powerful establishment become a central component of the network’s messaging strategy. This framing is particularly effective because it exploits legitimate concerns about media bias or institutional trustworthiness, further strengthening audience belief in their narratives.

Over time, these mutually reinforcing platforms amplify highly specific messages or claims, such as the narrative that “NATO provoked the war in Ukraine,” or the assertion that “U.S. laboratories are preparing for first-strike nuclear capabilities.” The repeated cross-citations and reinforcement through multiple platforms lend these messages an artificial but powerful veneer of factual credibility, making them resistant to correction or fact-checking, regardless of the absence of genuine empirical support.

This circular promotion model holds particular appeal for certain types of organizations and efforts. Activist groups, especially those with limited resources or limited mainstream reach but strong discipline in messaging, can leverage circular promotion networks to significantly amplify their influence. Disinformation campaigns, whether directly state-backed or indirectly state-aligned, find these networks invaluable for laundering credibility—allowing state-directed narratives to appear independent, grassroots-driven, or organically developed. Finally, ideological communities that perceive mainstream media, academia, or governmental institutions as fundamentally corrupt, compromised, or biased are especially receptive to circular promotional structures, as these networks affirm their pre-existing distrust and provide a self-validating alternative information ecosystem.

Evidence of LASG using circular promotion:

• LASG quotes and republishes content from sources like Grayzone, Strategic Culture Foundation, SouthFront, and RT — all of which cross-cite each other, including LASG.

• It has hosted events with figures (like Scott Ritter, Dmitri Trenin) who are deeply embedded in that circular network.

• LASG’s blog and bulletin links show a high concentration of content that originates in ideologically aligned “alt” media, which is then referenced as support for LASG’s framing.

• LASG frequently cites its own earlier bulletins as sources, sometimes treating them as conclusive evidence.

In short, LASG benefits from and contributes to a circular promotion network. It’s not always explicit or coordinated — but the effect is the same:

A feedback loop of credibility that reinforces a worldview regardless of external validation.

Implications

If the Los Alamos Study Group (LASG) is engaging in circular promotion as a primary means of establishing its legitimacy, this significantly impacts the nature and reliability of its policy arguments. Such arguments become inherently self-referential, even when initially based on verifiable facts or legitimate evidence. Rather than drawing from independently verified sources or rigorous external analysis, LASG’s narratives increasingly rely on internal validation from ideologically similar sources, creating a feedback loop that reinforces particular viewpoints without external challenge or verification.

Moreover, this practice creates a strongly siloed audience, one inherently predisposed to accept narratives presented as alternative or “outsider” perspectives. Such an audience is typically skeptical or even dismissive of mainstream critiques, interpreting any criticism or fact-checking from established institutions as attempts by a biased establishment to silence dissenting voices. Consequently, LASG’s audience becomes resistant to external input, further deepening the divide between its internal narrative and broadly recognized external realities.

As a result, LASG’s influence tends to be most substantial within its own narrative ecosystem—among networks of activists, alternative media outlets, and ideological allies—rather than among institutional decision-makers, policy analysts, or academic experts who rely on robust, independently validated evidence. While this does not imply that LASG’s information is necessarily incorrect or entirely unreliable, it clearly indicates that LASG’s perceived credibility is rooted primarily in ideological consistency and narrative coherence, rather than in rigorous, objective, or externally verified analysis.

The circular network in action

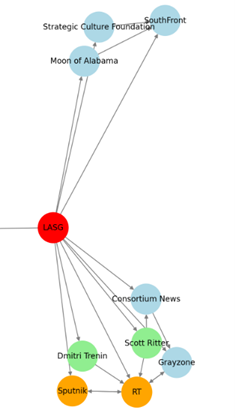

Here is a visual diagram showing the information network surrounding the Los Alamos Study Group (LASG) and its connections to alternative media and aligned figures:

• Red node: LASG (central hub).

• Blue nodes: Alternative media outlets (e.g., Grayzone, Consortium News).

• Orange nodes: Russian state media (e.g., RT, Sputnik).

• Green nodes: Individual commentators often featured in or aligned with the above outlets.

Arrows indicate directional influence or citation. Circular relationships between other outlets (e.g., RT and Grayzone) represent mutual amplification — a classic hallmark of narrative reinforcement loops.

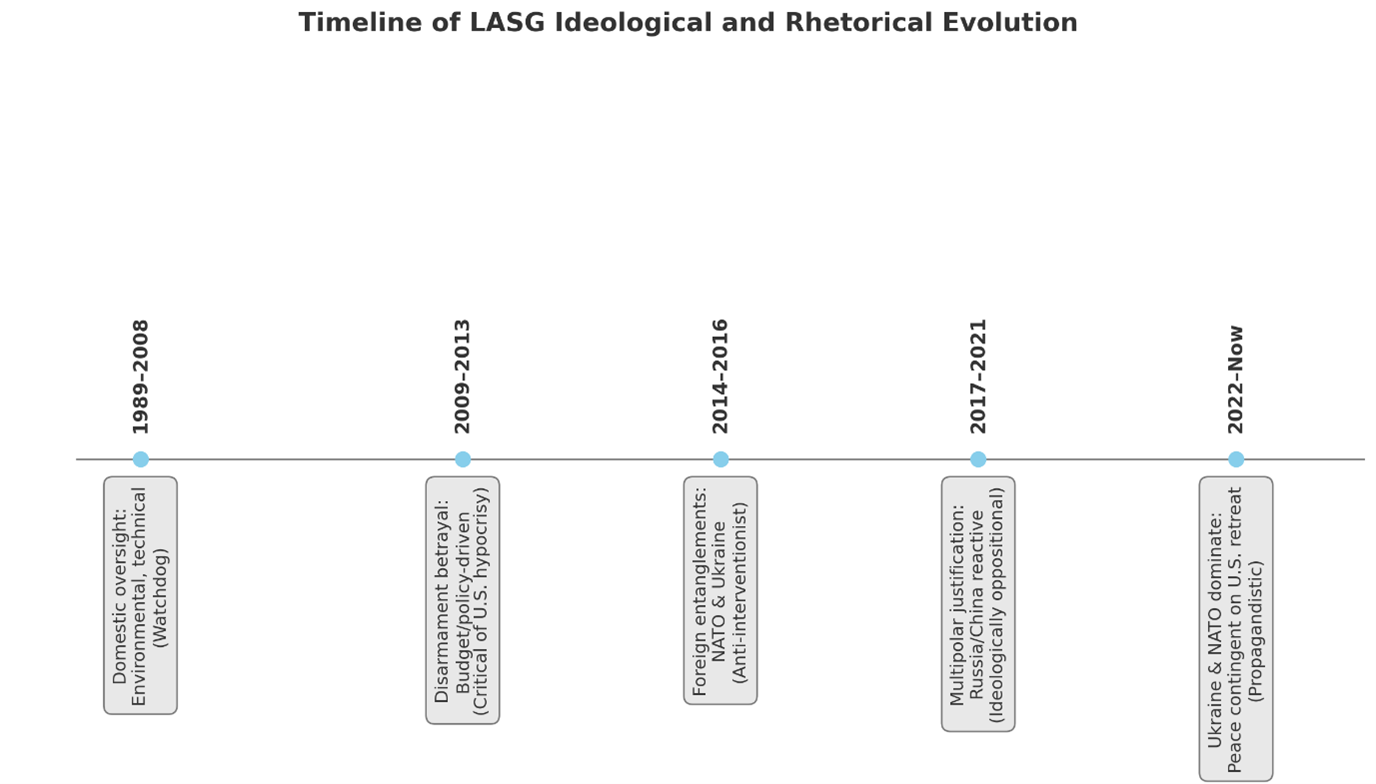

Where & When Did LASG Begin Shifting Toward Foreign Policy? – A Timeline of Reflexive Control

1989–2008: Domestic Focus

• Disarmament, cleanup, budget oversight.

• Messaging was technical, legalistic, and site-specific.

• No significant mention of U.S. grand strategy, NATO, or international conflict zones.

• LASG operated like an activist-analyst hybrid rooted in New Mexico nuclear facilities.

2009–2013: Budget Politics & U.S. Policy Critique

• Obama administration’s “nuclear modernization” sparked disillusionment.

• LASG began to frame nuclear policy in terms of:

o Military-industrial interests,

o Democratic hypocrisy,

o Betrayal of disarmament goals.

• Still no consistent foreign policy doctrine, but frustration with U.S. power began to dominate tone.

Inflection Point: LASG starts seeing nuclear issues as part of a broader system of imperialism.

2014: Ukraine Crisis = First Foreign Policy Lens

• LASG issues first bulletin linking Ukraine to U.S. strategy.

• Begins referring to Maidan as a coup, and NATO as aggressor.

• Slides from 2015 teach-ins reference:

o “Information war” framing,

o Western media propaganda,

o Russian gas pipelines and U.S. encirclement.

This marks the moment LASG begins using nuclear policy as an extension of anti-Western foreign policy critique.

2015–2021: Integration into Anti-Imperial Narrative

• Nuclear weapons policy now framed as part of:

o A neocon/U.S. strategy to dominate Eurasia,

o The reason Russia and China must defend themselves.

• LASG starts amplifying voices (e.g. Consortium News, Grayzone) that tie nuclear issues to:

o Syria, Libya, Ukraine, NATO, and the “multipolar world.”

• Public statements grow more ideologically rigid.

Foreign policy now shapes the rationale for disarmament — i.e., “if the U.S. weren’t so aggressive, there’d be no arms race.”

2022–Present: Foreign Policy Becomes Core Narrative

• Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine is immediately blamed on U.S./NATO.

• Nuclear disarmament arguments become conditional:

“There can be no disarmament unless the U.S. abandons imperialist strategies.”

• Bulletins focus more on:

o Geopolitical analysis than technical oversight.

o Criticism of Zelensky, NATO, Biden rather than DOE or LANL.

• Peace and arms control become framed as outcomes of U.S. geopolitical humility.

Around 2009, a notable shift occurred in the approach and rhetoric of the Los Alamos Study Group (LASG). Although there was no formal leadership transition—Greg Mello remained the leader of the organization—the broader political context changed significantly. Barack Obama’s administration, despite its initial messaging focused on disarmament, notably symbolized by Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize and the renowned Prague speech on nuclear disarmament, began to embrace nuclear modernization programs. For many anti-nuclear advocates, including Mello, this move felt like a profound betrayal. Rather than just critiquing the military-industrial complex as before, Mello increasingly perceived the arms control establishment itself—the very groups that once advocated nuclear restraint—as complicit in perpetuating nuclear arsenals and strategic competition.

This shift in political perspective coincided with a notable change in the rhetorical style of LASG’s public communications. The organization’s bulletins and public statements became sharply more confrontational and less nuanced, not only toward traditional targets such as the Department of Energy (DOE), but also toward other peace activists and mainstream media outlets. Greg Mello’s writing specifically took on a tone characterized by moral absolutism and ideological clarity, increasingly employing language that sharply criticized U.S. foreign policy and framed global nuclear issues through a broader geopolitical lens. This departure marked the point at which LASG began to prioritize moral and ideological framing over the previously more neutral, technical, and policy-driven analysis.

Concurrently, LASG began strategically positioning itself within a broader ecosystem of dissenting voices on foreign policy, an ecosystem that prominently featured outlets and commentators increasingly aligned with Russian or anti-Western narratives. The group began engaging more deeply with platforms and sources that emphasized narratives critical of NATO, skeptical of U.S. intentions globally, and sympathetic to Russian geopolitical perspectives. Over time, LASG’s messaging around nuclear disarmament and peace shifted noticeably, adopting positions that frequently mirrored or directly echoed these alternative narratives.

Key Points in LASG’s Trajectory:

• 2009: Disillusionment with Obama’s nuclear policies marks a rhetorical shift.

• 2014: LASG adopts framing consistent with Russian narratives on Ukraine.

• 2015–2021: Integration into broader anti-Western ecosystem (Grayzone, SCF).

• 2022–Now: Disarmament messaging fully reframed as contingent on U.S. retreat.

Interestingly, this ideological journey closely parallels the trajectory of another public figure, Scott Ritter, despite their vastly different backgrounds. Ritter, a former U.S. Marine and UN weapons inspector, initially gained prominence and credibility through his principled dissent against the Bush administration’s claims of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) in Iraq in the early 2000s. Initially celebrated for his courageous stance, Ritter’s narrative began to shift over the following decade. He became increasingly critical of U.S. foreign interventions and the broader military-industrial complex, eventually pivoting toward explicitly pro-Russian narratives. Since around 2016, Ritter has regularly appeared on Russian state-aligned media outlets such as RT and Sputnik, where he frequently promotes perspectives framing Russian military actions as defensive, labels Ukraine as a Western puppet state, and sharply critiques NATO and Western media as corrupt and propagandistic.

Greg Mello’s own path—from a technically credible nuclear watchdog to a voice deeply enmeshed in geopolitical and anti-Western framing—mirrors Ritter’s ideological evolution. Mello initially built his credibility on environmental advocacy, rigorous nuclear safety oversight, and successful legal interventions, most notably contributing to halting the development of the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement – Nuclear Facility (CMRR-NF) at Los Alamos. However, following his disillusionment with Obama’s nuclear policies, Mello increasingly adopted a starkly ideological approach. Beginning around 2014, he and LASG actively engaged with narratives describing NATO expansion as an existential threat to Russia, casting Western media coverage as deeply biased and inherently “Russophobic,” and arguing explicitly that nuclear disarmament and peace were impossible unless predicated upon a retreat in U.S. geopolitical influence.

The points of convergence between Ritter’s and Mello’s trajectories are striking. Both began their respective journeys as credible and principled dissenters, operating from within or adjacent to established U.S. policy structures. Both experienced profound disillusionment, rooted in a perceived betrayal by political leadership or mainstream institutions. This disillusionment led them toward an increasingly ideological position—one defined by moral absolutism and a binary worldview where the United States and NATO were portrayed unequivocally as aggressors, and Russia as reactive and defensive. Furthermore, both figures found reinforcement and validation in alternative media ecosystems, particularly those explicitly or implicitly aligned with Russian state narratives. Within these ecosystems, their narratives were celebrated and amplified, further solidifying their ideological positions and providing an emotional payoff in terms of purpose, community, and continued relevance.

On a psychological level, both Ritter and Mello developed a powerful sense of moral certainty, convinced that they alone—or their closely aligned groups—were clearly seeing and articulating the truth, while mainstream and opposing views were inherently compromised or corrupted. This form of moral absolutism, though initially rooted in integrity, gradually hardened into ideological rigidity, restricting openness to contradictory evidence or nuanced critique.

Additionally, both experienced significant rejection and alienation from mainstream institutions, media outlets, and academic circles, once environments that recognized their valuable critical contributions. Rather than prompting self-reflection, this rejection only reinforced their conviction in the righteousness of their positions. Such reinforcement is a hallmark of ideological radicalization, where external criticism is interpreted as validation of correctness rather than a signal to reassess beliefs.

Finally, the common fixation on what they viewed as systematic “Western lies” completed their ideological alignment. Both Ritter and Mello shifted from nuanced critiques of specific U.S. policies toward wholesale condemnation of the West as uniquely corrupt, inherently aggressive, and morally bankrupt. Crucially, neither applied the same rigorous critique or scepticism toward opposing powers, notably Russia, whom they increasingly portrayed as justified, defensive, or misunderstood actors reacting rationally to Western provocation.

In sum, both Ritter and Mello began their trajectories grounded in principled, evidence-based dissent, driven initially by integrity and genuine critique. However, a combination of frustration, isolation, ideological reinforcement from alternative media, and moral absolutism eventually led both into adopting polarized and adversarial worldviews. This ideological shift, embedded in a narrative ecosystem that rewards anti-Western framing regardless of nuance or factual precision, transformed them from insightful critics into powerful voices amplifying foreign-aligned narratives—often without overt coordination or direct intent. Their parallel journeys illustrate the subtle but potent risks of ideological capture and demonstrate vividly how legitimate dissent can evolve into a vehicle for strategic propaganda.

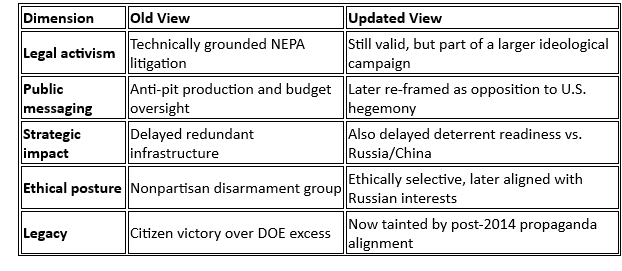

The Success of LASG – Reevaluated

The story of how the Los Alamos Study Group (LASG) contributed significantly to stopping the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement – Nuclear Facility (CMRR-NF) represents a classic example of how a relatively small watchdog organization can leverage legal tools, detailed research, and public advocacy to achieve substantial policy outcomes. The CMRR-NF was a massive nuclear infrastructure project proposed at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), primarily designed to support increased plutonium pit production, a core component for nuclear weapons. Initially budgeted at approximately $375 million, the projected costs ballooned dramatically, eventually surpassing $5 billion. This facility, if completed, would have significantly expanded the nuclear warhead production capabilities at LANL.

LASG’s opposition began with meticulous research and strategic use of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). From 1999 to 2005, LASG carefully monitored developments related to the CMRR-NF, identifying critical issues such as rapidly escalating costs, incomplete and outdated environmental reviews, and insufficient justification for increased plutonium pit production. Their ability to uncover internal Department of Energy (DOE) and National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) documents provided LASG with documentation superior even to what was accessible by congressional staff and mainstream journalists.

Building on this research, LASG undertook legal action based on the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Between 2006 and 2011, they litigated against DOE and NNSA, arguing convincingly that the original 2003 Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was obsolete due to escalating budget estimates, increased seismic risks, and significant changes in technical plans. Though initially resistant, DOE eventually conceded to LASG’s demands in 2011, committing to a Supplemental EIS. While the court eventually dismissed the lawsuit as moot, the legal victory achieved LASG’s objective: forcing the government to revisit the planning and approval process, effectively delaying the project.

In parallel, LASG provided compelling technical and budget analyses during the litigation period. Their reports highlighted the redundancy and strategic irrelevance of the proposed facility, pointing out that the United States already maintained a substantial surplus of plutonium pits, rendering additional production unnecessary. Furthermore, affidavits from former nuclear weapons engineers, such as Robert Peurifoy from Sandia Laboratories, bolstered their arguments, contending that the CMRR-NF facility offered no tangible benefit to national security or deterrence capabilities. LASG’s arguments resonated with influential institutions, including the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the Congressional Research Service (CRS), further amplifying pressure on policymakers.

Beyond the technical and legal fronts, LASG mobilized significant political and public opposition from 2010 to 2012. By engaging local activists, environmental organizations, and fiscal watchdog groups, LASG amplified the political toxicity of the project. Highlighting its wasteful spending during the sensitive period of economic recovery following the 2008 financial crisis, LASG succeeded in framing the facility as both financially irresponsible and contrary to President Obama’s stated disarmament policies.

This multifaceted strategy culminated in a definitive outcome: the formal cancellation of the CMRR-NF project in 2014, following its initial deferment in 2012. NNSA opted instead to handle plutonium pit production through upgrades to existing facilities and alternative locations, such as the Savannah River Site. This cancellation was widely recognized as a major victory for LASG, acknowledged publicly by oversight bodies and media institutions.

However, this success story demands re-examination in light of LASG’s subsequent ideological trajectory. By 2014–2015, LASG had visibly shifted from a technical watchdog stance toward a distinctly anti-Western geopolitical framing. Increasingly aligning its messaging with narratives frequently associated with Russian disinformation, LASG began promoting positions critical of NATO expansion, U.S. foreign policy in Ukraine, and broader Western geopolitical strategies. This shift prompts critical questions about the group’s foundational motivations and strategic alignments.

Although no evidence suggests LASG acted directly under foreign guidance during the CMRR-NF campaign, the group’s longstanding exclusive focus on criticizing U.S. deterrence capabilities, paired with notable silence regarding nuclear developments in Russia and China, indicates a predisposition toward positions aligning with Russian strategic interests. In strategic terms, halting CMRR-NF can now be viewed not merely as an environmental or disarmament victory but also as inadvertently serving broader Russian geopolitical goals by weakening U.S. nuclear infrastructure and strategic coherence within NATO.

Thus, while LASG’s early success against CMRR-NF remains undeniably rooted in valid technical critiques and legal actions, it must now be contextualized within their later ideological evolution. LASG’s trajectory from credible watchdog to propagator of narratives aligning with foreign adversarial interests illustrates how initially legitimate advocacy can become intertwined with strategic propaganda efforts, even without explicit coordination or intent. This perspective underscores the complex relationship between genuine domestic activism and geopolitical information warfare using reflexive control. To summarize:

The CMRR-NF case, re-examined honestly in the light of our discoveries:

• Stopping a U.S. nuclear facility: Sounds like a disarmament win.

• But when the same organization later:

o Blames NATO for Russia’s war in Ukraine,

o Platforms known Kremlin-aligned voices,

o Cites state propaganda outlets uncritically,

o Fails to condemn Russian nuclear threats,

o Ties all nuclear disarmament to Western capitulation…

then you have to reassess their motives, not just their methods.

Why the obvious answer matters:

LASG’s pattern mirrors a known strategy:

• Exploit open societies’ activism (legal tools, press freedoms, anti-war sentiment),

• Use legitimate critique of Western policies to erode deterrence and internal trust,

• Avoid symmetrical criticism of authoritarian nuclear powers,

• Shift from watchdog to ideological weapon.

That’s what LASG did — and the success in stopping CMRR-NF becomes, retroactively, part of that arc.

Even if they weren’t acting on instructions, they internalized and promoted a narrative that mirrors Russian strategic propaganda.

In other words:

They weren’t agents — but they were instruments of the kind of asymmetric narrative warfare Russia cultivates.

And if they’re still using their earlier credibility to:

• Undermine support for Ukraine,

• Promote nuclear disarmament conditional on U.S. geopolitical retreat,

• Deflect criticism from authoritarian states…

Then that earlier success should no longer be viewed in isolation.

It’s time to stop calling it “alignment” and call it what it is:

An ideological transformation that now serves the goals of authoritarian disinformation.

In the next article we will examine formal and informal co-operation between Russia and Iran and re-evaluate another case widely reported, that of the “White Helmets”, using publicly available data and tools.

No responses yet