by Susanne Berger and Ruben Agnarsson

January 17, 2025

80 years after Raoul Wallenberg’s disappearance, the problems of gaining access to specific records concerning the Swedish diplomat in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other relevant collections in Swedish archives continue. Foreign Ministry officials say they have no idea which information is still classified and show no interest in finding out.

A few years ago, Gudrun Persson, one of Sweden’s leading experts on Russia and national security policies, summarized the problems with historical archives: Instead of simply accepting the

information they contain at face value, Persson argued, researchers should consider it their main task to determine what has been left out. To illustrate her point, she told an anecdote about a high-level Russian diplomat who scolded his novice colleagues who submitted a verbatim account of an official meeting for his scrutiny. “Young idiots! You are not supposed to write down what was said, you are supposed to write down what ought to have been said.” [1]

The complexity of archival collections

The problems that Persson describes are obviously not limited to Russia. In 2019, the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs formally announced that a total of 170,000 pages of documents in his case were now available to the public. In her official statement, Foreign Minister Margot Wallström announced that only 230 pages in the Foreign Ministry’s official Wallenberg dossier were still classified. The message was clear: the Swedish government has nothing more to say on the subject.

Wallström’s statement obscures the fact that the official Raoul Wallenberg case file is far from complete. Serious misconceptions persist about how the documentation of the Wallenberg case is organized.

Not all relevant records are stored in the official case file at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Only a limited part is archived there. Thousands of documents that may be of great interest to the Wallenberg investigation are held in other collections in the Foreign Ministry, as well as in other Swedish archives. In addition to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, several other Swedish authorities maintain their own separate Raoul Wallenberg dossiers, such as the Swedish Security Police (SÄPO).

The Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs refuses to identify classified documents

When researchers and journalists requested that the remaining, still censored 230 pages of the Raoul Wallenberg case file be declassified, they were told that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs cannot identify the information. According to Tobias Thyberg, head of the Department for Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EC) which oversees the Wallenberg case, classification is “fluid” and “varies”, and identifying the data would require a complete review of all 170,000 pages – a task that exceeds the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ capacity, Thyberg argued. If researchers wanted to locate the still classified 230 pages, Thyberg added, they should conduct their own private review.

Thyberg’s response is puzzling, to say the least. In 2019, the 230 documents were handed over in censored form to Raoul Wallenberg’s nieces Marie Dupuy and Louise von Dardel by Berndt Fredriksson, former permanent secretary at the Foreign Ministry’s Secretariat for Security, Secrecy and Preparedness (sekretariat för säkerhet, sekretess och beredskap, UD/SSSB). Can Thyberg, as head of the Eastern European department, really be unaware of this fact? Perhaps even worse is the possibility that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has no clear idea of which documents in its own case file are currently secret. Either way, it indicates an acute disinterest and a reluctance to aid researchers and journalists (not to mention Wallenberg’s family) in their work. [2]

We have asked Swedish officials for full declassification of the 230 pages and requested further clarification on how exactly the Foreign Ministry identifies and tracks classified information in the Wallenberg case file and related collections, especially documentation carrying the designation “top secret” or beyond; internally and in other Swedish archives.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs obviously simply wants the whole case to go away – which is also indicated by the fact that an online database containing thousands of documents about the Raoul Wallenberg case from Swedish and Russian archives has now been shut down for four years despite repeated requests and reminders from researchers and Raoul Wallenberg’s family. Swedish officials have offered no explanation and do not respond to inquiries in any substantive way.

Unclear criteria for handling and disclosing confidential information

The Foreign Ministry’s actions can be compared to the response to a request for access to SÄPO’s Raoul Wallenberg archive in the National Archives. The archivists immediately offered a review, but then another problem arose: the archivist did not want to disclose how many pages remain secret because that information is itself classified. When we asked for an explanation, none was forthcoming.

In September, the same question was submitted to National Archivist (Riksarkivarie) Karin Åström Iko at the Swedish National Archives (Riksarkivet), during the Raoul Wallenberg International Roundtable in the Swedish Parliament on September 18, 2024. (Despite repeated invitations, no current official from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs attended the seminar). Åström Iko stated that when it comes to the issue of confidentiality, archivists must adhere to the Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act (2009:400). [3]

In December 2023, a group of Swedish historians criticized the strict interpretation and often flawed application of the law when it comes to World War II and the immediate post-war period.

Iko admitted that the decision-making process is somewhat subjective and also regularly involves consultations with external authorities, such as various ministries in the Swedish Government Offices. The National Archives has still not answered the historians’ questions and criticisms.

Circumventing Sweden’s “principle of openness”

A central problem for the Wallenberg inquiry and other official investigations (such as the recent review of Swedish authorities’ official handling of the COVID crisis) is that some sensitive information is not archived at all – an unintended consequence of Sweden’s much-vaunted “principle of openness” [offentlighetsprincipen], which minimizes legal rules for keeping public information secret. [4]

Eva Britta Wallberg, former Chief Archivist (Arkivråd) at the Swedish National Archives, warned of the growing problem of correctly archiving public records as early as 2004, in her seminal paper Att undvika offentlighetsprincipen (Avoiding the Principle of Openness). [5]

At the time, Wallberg expressed serious skepticism that the digital age would bring any improvement in the efficiency of preserving documents. On the contrary, Wallberg wrote, “It is more likely that modern organization, with its digitalized information and rapid changes, increases the risks of losing information and that, in future, we will get still more archives with no real historical significance.”

The Swedish Foreign Ministry often archives documents with the designation “confidential” or “secret” separately, in specially designated folders (“working papers” [arbetspapper]; “red folder” [röda pärmen] etc.); or safes (“yellow safe” [gula skåpet]) – like, for example, the discussions during the years 1965-1974 about a possible exchange of the Soviet agent Stig Wennerström for the truth about Wallenberg’s fate. These documents were to be placed later on in the Raoul Wallenberg case file but were archived instead in more general collections. [6]

Private collections pose another serious challenge for researchers. Laws governing public access do not apply to these archives. As Wallberg pointed out, placing controversial documents in private archives has been another way for some [Swedish] authorities to protect information from public scrutiny, especially in the defense and business sectors. [7]

The failure to properly register and archive highly relevant documents

It seems that Wallberg’s predictions have largely proven to be correct, because even in the case of Raoul Wallenberg, some highly relevant documentation was never formally registered or archived at all.

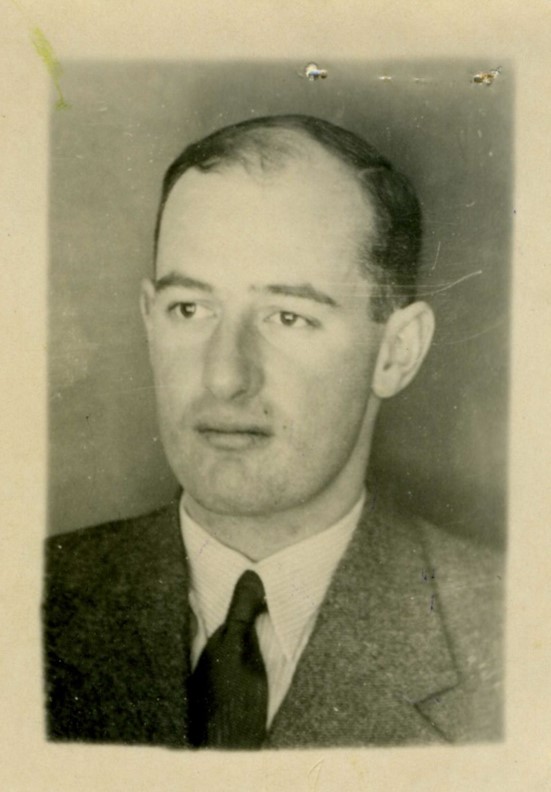

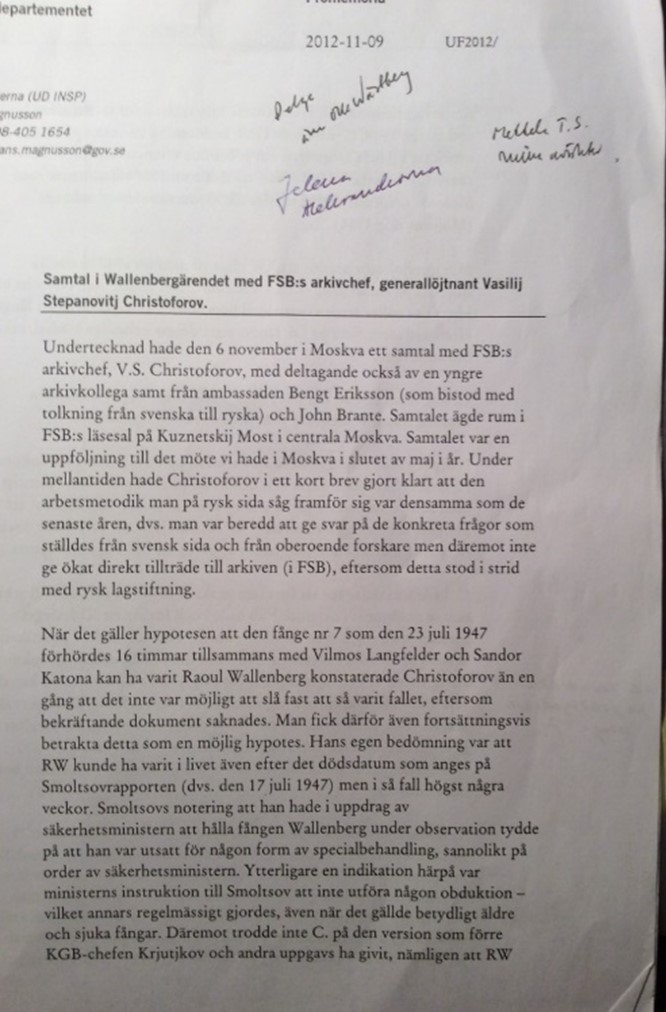

The documents in question concern top-level discussions held between Swedish and Russian officials in 2011–2012. The conversations concerned the sensational information that Raoul Wallenberg was possibly being held as a numbered prisoner (prisoner no. 7), six days after his official death date of July 17, 1947. The documents consist of two memos and a draft letter by Swedish Ambassador Hans Magnusson, who in 2012 conducted an official review of the Raoul Wallenberg case.

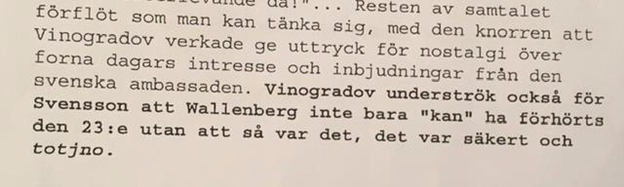

The documents showed that two senior officials of the FSB (Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation, successor to the KGB) – Colonel Vladimir K. Vinogradov and his superior, Lieutenant General Vasily S. Khristoforov – confirmed that Raoul Wallenberg was almost certainly identical to the as yet unidentified prisoner No. 7 who was interrogated for more than 16 hours on July 23, 1947, in the Internal (Lubyanka) Prison in Moscow.

The two FSB officials concluded that Wallenberg “may have been alive after his official date of death [July 17, 1947], as stated in the so-called Smoltsov Report, but in that case for a few weeks at most.” Swedish officials did not follow up the remark and did not insist on further clarification.

In a separate conversation, Colonel Vinogradov informed Swedish officials that it was not only possible that Raoul Wallenberg was interrogated on July 23, 1947, but that this was tochno – a fact. The information was immediately classified. [8]

The memorandum containing Vinogradov’s statement was initially not included in the 40,000 pages of the Raoul Wallenberg case released by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in August 2019. This crucial information was also not shared with Raoul Wallenberg’s family, researchers or the public. [9]

Two other documents – a memo and Ambassador Magnusson’s above-mentioned draft letter in which he references the new information – were never archived in the Foreign Ministry’s archives in any form (!). Magnusson also did not include this information in his official report in 2013. Instead, researchers learned of the documents’ existence by pure chance.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs refused to answer the question of how Raoul Wallenberg’s family, researchers and journalists can be sure that no other highly relevant documentation or information has been handled incorrectly and what measures the Ministry has taken to ensure that such omissions do not occur in the future.

The failure to properly file the above-mentioned records is not a trivial matter. The indication that Raoul Wallenberg may have been alive after his official death date was one of the most sensational pieces of information to emerge in the official investigation of his case since 1945. In addition, it is now clear that Russian officials deliberately withheld this and other key information for decades, including from the official investigation conducted by the Swedish Russian Working Group (1991–2001) in which Raoul’s brother (Dr. Guy von Dardel) participated. However, instead of forcefully insisting on full disclosure, Swedish officials seem to have accepted the claims of Russian officials that they have no further information that could shed light on the full circumstances of Raoul Wallenberg’s fate — despite strong indications to the contrary.

Swedish officials consciously left Raoul Wallenberg to his fate

In recent years, it has become clear that – contrary to previous claims – the Swedish government’s lack of determined action on Raoul Wallenberg’s behalf was not just the result of a set of unfortunate circumstances, i.e., chaotic post-war conditions, individual incompetence, Wallenberg’s status as an “outsider” or Sweden’s overwhelming fear of the Soviet Union. Instead, Swedish officials seem to have consciously abandoned Wallenberg immediately after his disappearance. The reasons for this decision have not been fully explained. [10]

The most crucial question remains: Why was Raoul Wallenberg simply abandoned to his fate, especially during the crucial year of 1946 when Soviet leader Josef Stalin showed a more conciliatory attitude towards Sweden and when there were relatively strong indications that Raoul Wallenberg could still be alive? In 1946, Swedish officials prioritized a major Swedish Soviet trade agreement, while failing to use the opportunity to insist on a complete resolution of Wallenberg’s disappearance. Instead, Swedish officials made at least three formal requests to the Soviet leadership to declare Raoul Wallenberg dead.

Sweden had strong motives for appeasing Soviet officials. Swedish businessmen, and especially the Wallenberg business empire, risked losing tens of millions of dollars in lost assets in Soviet-occupied territories. The compensation talks took years to conclude. A public scandal in the form of a possible show trial featuring Raoul Wallenberg could have seriously jeopardized Sweden’s reputation and future Swedish interests.

Swedish officials also had other reasons to be concerned. Virtually all documents about highly sensitive Swedish intelligence operations in Hungary during the years 1943–45 have disappeared from Swedish archives. [11] The operations were much more extensive than previously understood and were at least partly directed against the Soviet Union. These actions may have seriously compromised Raoul Wallenberg in both Swedish and Soviet eyes. Sweden was officially neutral at the time and represented Soviet interests in Hungary.

As early as March 1947, Wallenberg’s mother, Maj von Dardel, was so upset by the passive attitude of Swedish officials that she marched into the Foreign Ministry and demanded to know why the Ministry’s diplomats assumed that her son was no longer alive, when they had received no clear evidence for his death. In a tense meeting, she sharply criticized their “lack of enthusiasm” and characterized the official handling of her son’s case as “cold-blooded.”[12]

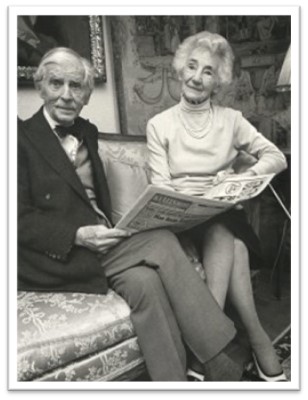

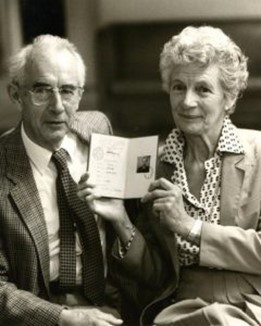

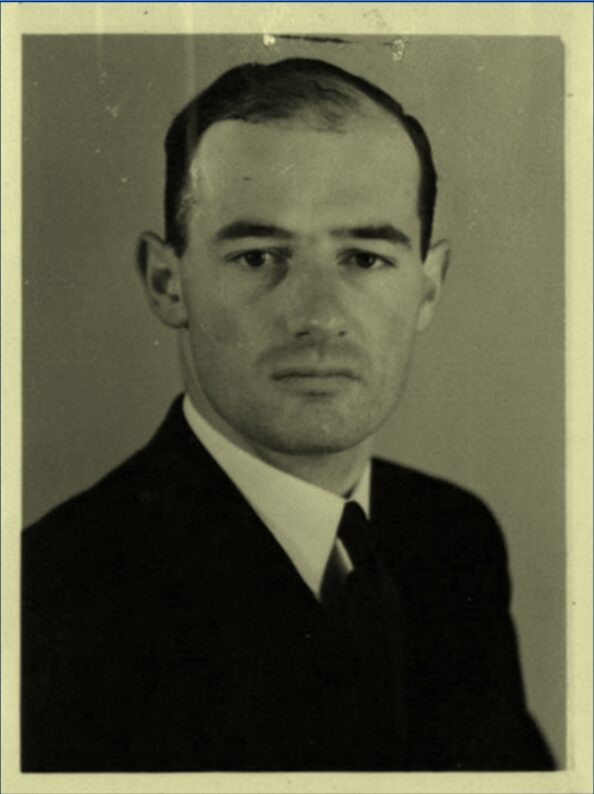

Raoul Wallenberg’s parents Fredrik and Maj von Dardel fought for more than thirty years to learn what had happened to their son, until their deaths in 1979. Wallenberg’s siblings Guy von Dardel (left) and Nina Lagergren (right), pictured here holding their brother’s diplomatic passport in Moscow in 1989, continued the fight well into the 2000s.Source: Guy von Dardel, private archive.

Strictly secret

It is quite startling that almost all information contained in the archive of the Swedish Security Police concerning two top Swedish diplomats – Sverker Åström, a former Cabinet Secretary and Ambassador to the U.N., and Rolf Sohlman, the longtime Swedish Ambassador to Moscow (1947-1963) – remains entirely classified. It is unclear why not even partially censored documents can be released, as is a common practice in other international archives, including those of the CIA in the United States.

Both Åström and Sohlman played a central role in the official handling of the Raoul Wallenberg case for decades. Both were suspected of being Soviet assets for many years. In 2021, SÄPO rejected a request from researchers and members of Raoul Wallenberg’s family (Marie Dupuy and Louise von Dardel) to review Mr. Åström’s personal file, as were their subsequent appeals. [13] Strangely enough, SÄPO did not even want to answer the simple question of whether the accusations against Mr. Åström are true or false (or possibly inconclusive) – a statement that would in no way involve the release of still secret information. A request to the National Archivist Karin Åström Ito for clarification yielded no result.

The request for full access to Ambassador Sohlman’s file is crucial because in the early 1960s, SÄPO suspected that the ambassador’s long-term confidential contact to the Soviet leadership involved one of the KGB’s most notorious counterintelligence officers and recruiter of foreign agents. For more than three years, the two men discussed the most sensitive issues of state, including new and at the time highly secret information in the Raoul Wallenberg case. Hundreds, if not thousands, of pages chronicling their discussions must be preserved in the archives of the FSB. These collections of documents were never made available to previous investigations and may contain crucial background details about the official Russian handling of the Raoul Wallenberg case. It should also be noted that the decisive clue regarding this information came from previously classified Swedish documents.

In their appeal in January 2023, Dupuy and von Dardel argued that the question of possible undue Soviet influence in the postwar Swedish foreign policy apparatus is of central importance to their continuing efforts to establish the full circumstances of Raoul Wallenberg’s disappearance in 1945: “The family’s right to the truth as well as our need to learn all the facts about Åström’s and Sohlman’s contacts with Soviet representatives should outweigh any lingering national security or privacy concerns.”[14]

Other potential gaps in the official case record

It is also worth noting that few if any records from Swedish foreign or military intelligence agencies (T-Kontoret, GBU, SSI, KSI, MUST, FRA) for the years after 1965 have so far been released. Important events such as the arrest of Soviet agent Stig Wennerström in 1963 and subsequent events, the collapse of the Soviet Union and Raoul Wallenberg’s family’s visit to Moscow in 1989 should have generated formal reporting and assessments by Swedish intelligence personnel. [15] The available documentation so far comes mainly from the Swedish Security Police or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It is also still unclear how many Swedish citizens, including Swedish agents, were imprisoned in the Soviet Union after 1945 and where and for how long exactly these individuals were held. The information would have been crucial for correctly evaluating witness information in the Wallenberg case and other unsolved disappearances. [16]

Through the years, foreign governments have requested that certain information about Sweden’s Wallenberg investigation be kept secret. This is what the Israeli government did in the early 1980s, for example, when it was reluctant to provide details about certain witness statements. Officials feared that this information could reveal the nature and scope of Israeli intelligence activities behind the Iron Curtain. Countries such as Russia, the United States or the United Kingdom may well have turned to Sweden with similar requests. When asked if Sweden in turn has ever asked other governments to withhold certain information or documentation in the Raoul Wallenberg case, Swedish officials did not issue a clear denial but simply stated that they are “not aware” of any such requests.

An inherent conflict of interest

As new findings indicate, it is becoming increasingly clear that additional, truly relevant information is available in both Russian and Swedish archives and that the question of what happened to Raoul Wallenberg can almost certainly be solved.

From the outset, the official Wallenberg investigation has been characterized by an inherent conflict of interest. While the sole focus of Wallenberg’s family was to establish the whole truth about his fate, the primary interest of Swedish officials was to avoid any collateral damage and to solve the case simply to the point where they could remove it from the official Swedish Russian agenda.

This suggests that Sweden never committed itself to solving the disappearance of Raoul Wallenberg – one of its most celebrated citizens who disappeared while carrying out an official mission for the Swedish state – as a matter of principle. Instead, the Swedish government signaled very early on to Soviet officials that it was primarily interested in getting rid of the problem and that it was quite satisfied with an incomplete investigation. This theme has now run like a red thread through the Wallenberg investigation for eight decades.

From 1945 to the present, the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs has repeatedly failed to meet its obligations under both civil and international law. In defense of their own passivity, Swedish officials continuously argue that “the Swedish Foreign Ministry does not conduct any research of its own about Raoul Wallenberg”– as illustrated by the former Foreign Minister’s written answer in the Swedish Riksdag on December 16, 2020 , [17] and most recently by the current Foreign Minister in the Riksdag’s “frågestund” [question time] on October 17, 2024. [18] The argument is disingenuous because, after all, it was the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that abandoned Raoul Wallenberg, then went on to conceal its actions and still today continues to withhold important information that family, researchers, journalists and the public are requesting. It also means that, in reality, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs leaves researchers and the Swedish diplomat’s family to shoulder the burden of research efforts by themselves, including the lion’s share of research costs.

A controlled investigation

During the 1990s, both Swedish and Russian officials maintained a narrow and sharply limited focus in the Wallenberg investigation. Both sides deliberately misrepresented and omitted important information in their respective reports and failed to provide access to key documentation to researchers and Wallenberg’s family.

Just as important is the question whether there has been a spoken or unspoken understanding and/or possible coordination between Swedish and Russian authorities in order to keep the investigation within closely guarded boundaries to protect special interests and to avoid sensitive disclosures. The possibility must be seriously investigated. Such an investigation should occur quickly, since institutional knowledge of the Wallenberg case and other Cold War mysteries is fading quickly in both Sweden and Russia.

The idea that the direction and possibly the outcome of Sweden’s Raoul Wallenberg investigation since 1945 may have been largely controlled and predetermined is a troubling thought.

If Raoul Wallenberg and other Swedish citizens who were missing in the Soviet Union were deliberately left to their fate, it would not only constitute a serious moral failure but could potentially rise to the level of obstruction and even criminal neglect.

In April 2023, the Swedish ambassador to Israel, Eric Ullenhag, took the extraordinary step of formally apologizing to Raoul Wallenberg’s family “for the Swedish government abandoning him and leaving his family far too alone and without the support they deserved.” Unfortunately, the problems continue to persist. Today, many families of current Swedish political prisoners – Swedish citizens illegally imprisoned or missing abroad – find themselves in a similar battle with Swedish authorities that Wallenberg’s family fought eighty years ago.

Wallenberg deserves better

The protection of the fundamental human rights of individual citizens is central to the defense of democratic values. It was this commitment that formed the very core of Wallenberg’s humanitarian activism in 1944, and it retains the greatest possible relevance and consequence today.

Sweden’s abandonment of Raoul Wallenberg created a national trauma, with the result that his and the Swedish Foreign Ministry’s bureaucratic resistance to the Holocaust has not received its rightful place in Swedish historiography. It remains a startling fact that Wallenberg’s important legacy (which is also that of Sweden!) continues to be far more celebrated abroad than in his home country.

Raoul Wallenberg, his family and Sweden as a country deserve better – after eight decades, it is time for the Swedish government to provide full disclosure of all aspects of his case.

Susanne Berger is a Senior Fellow with the Raoul Wallenberg Centre in Montreal, Canada. She served as a consultant to the Swedish Russian Working Group that investigated Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg’s fate in Russia (1991-2001). She is the founder and coordinator of the Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative (RWI-70).

Ruben Agnarsson is a journalist and author who has written for decades about Sweden’s role during the Cold War and about security policy aspects surrounding a number of key events during this period. Last fall, he published the book (in Swedish) ”Sweden’s Finest Hour – Raoul Wallenberg and Sweden’s Bureaucratic Resistance to the Holocaust”.

REFERENCES:

- On June 29, 2022, Gudrun Persson, Swedish Radio, sommarprat. The Russian diplomat quoted is Oleg Grinevsky, the former Russian ambassador in Stockholm 1991–97. [minute 4:15:00 – 5:00:00]

- The Foreign Ministry’s decision was appealed to the government this past October 24th. Not surprisingly, the appeal was rejected (regeringsbeslut [government decision] UD2024/14339, December 05, 2024) It appears doubtful that the government was aware of the fact that the set of 230 still censored documents can be easily identified.

- On 23 October, Karin Åström Ito received a written reminder of the specific questions that were asked during the Riksdag seminar. Her written answer, delivered on 21 December, did not expand on her pervious responses. The Swedish Foreign Espionage Act [lagen om utlandsspioneri] that went into effect in January 2023 may pose additional obstacles to releasing certain types of details. The law criminalizes the disclosure of any information that could affect Sweden’s relations with its allies or other foreign partners .

- Inga-Britt Ahlenius. Utan dokumentation kan ingen granskas. [Without documentation there can be no investigation] Svenska Dagbladet, June 26, 2022.

- Kungliga Krigsvetenskapsakademiens Handlingar och Tidskrift. The Royal Swedish Academy of War Sciences’ Documents and Journal. December 8, 2004.

- Some of the documents were archived in the archive at the Swedish embassy in East Germany. A recent example is a document from 1945 that was discovered in a special safe at the Swedish Ministry of Finance only in 2008, 70 years after it was received. It is a letter dated April 21, 1941, from Ernst Herslow, director of Skandinaviska Banken to Ernst Wigforss, then Swedish Minister of Finance. The letter concerned the extension of Swedish bank credits to German shipbuilding companies, in return for payment to Swedish business partners, in order to facilitate the construction of several ships for Nazi Germany. Wigforss, like his successors, apparently considered the matter to be highly sensitive. The letter was never formally registered in the Foreign Ministry’s archive and was never placed in its official collections. See Bo Hammarlund and Krister Wahlbäck. Arkivfynd avslöjar beslutet om första svenska krediten till Nazityskland. [Archive discovery reveals the decision regarding the first Swedish credit to Nazi Germany]. Klara, 2009; see also Peter Vinthagen Simpson. Sweden Approved Secret Nazi Loan: Report. The Local, February 15, 2009.

- ”Inom det svenska försvarsetablissemanget har det förekommit att kontroversiella papper har betraktats som enskild egendom. För den vetenskapliga forskningen har viktiga privata arkiv skapats på det sättet, arkiv som i realiteten innehåller officiella handlingar och borde ha underställts befintlig lagprövning.” [Within the Swedish defense establishment, there have been cases where controversial papers have been regarded as private property. For scientific research, important private archives have been created in this way, archives that in reality contain official documents and should have been subject to existing legal review.]

- A note allegedly written by Dr. Aleksandr Smoltsov, head of the medical department of Lubyanka prison, in 1947. The note was addressed to MGB Minister Viktor Abakumov. It stated that “a prisoner Walenberg [one letter “l” in the original]” had died of “a heart attack” on July 17, 1947, in his cell in Lubyanka prison. The note was released in February 1957, as part of the so-called Gromyko Memorandum, named after Andrei Gromyko who was the Soviet Union’s Deputy Foreign Minister at the time.

- A likely reason for not wanting to acknowledge or follow up on the information was the fact that the Swedish government did not want anything to distract from the 2012 centenary celebrations, which marked Raoul Wallenberg’s 100th birthday. The celebration focused almost exclusively on highlighting his humanitarian mission in Hungary. According to handwritten notes on the documents, Ambassador Magnusson [or other Swedish diplomats] informed Olle Wästberg, former Swedish Consul General in New York, about the content of his discussions with Khristoforov. At the time, Wästberg was one of the Swedish officials responsible for organising the centenary celebrations..

- The 2004 final report of the so-called Eliasson commission that investigated the official Swedish handling of the Raoul Wallenberg case since 1945 omitted and misrepresented several important facts. For example, investigators claimed that the 1946 negotiations for a large Swedish Soviet credit and trade agreement did not seriously impact official Swedish actions in the Wallenberg case. This is because in the Commission’s view, the decisive phase of the negotiations for the agreement began only in August 1946, two months after Wallenberg’s fate most likely had been decided. Already on June 15,1946 the Swedish Ambassador in Moscow, Staffan Söderblom asked the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin during a rare personal audience to confirm that Wallenberg was no longer alive. However, the commission’s assessment is problematic. A high-level official Swedish trade delegation traveled to Moscow as early as the end of May 1946 to begin the credit negotiations. Staffan Söderblom accompanied the group. Therefore, the issue of the credit and trade agreement was very much on the official Swedish Soviet agenda right at the time of the meeting between Ambassador Söderblom and Stalin and clearly impacted the discussions in the Wallenberg case. The Commission also falsely asserted that Söderblom acted independently, without knowledge or instruction from his superiors. See Ett Diplomatiskt Misslyckande: Fallet Raoul Wallenberg och den Svenska Utrikesledningen. [A Diplomatic Failure: The Raoul Wallenberg Case and the Swedish Foreign Policy Leadership.] Statens offentliga utredningar (SOU) 2003:18 https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2003/02/sou-200318-/. See also https://www.fritz-bauer-forum.de/en/raoul-wallenbergs-fate-and-a-swedish-billion-kronor-loan-to-the-soviet-union/; and https://www.fritz-bauer-forum.de/en/they-didnt-want-him-back/

- This is also the case for information about contacts with British intelligence. Brittisk underrättelsetjänst och sabotageverksamhet [British intelligence and sabotage activities]. F VIII e 16.8, 1942–54.

- She criticized their “cold-mindedness and lack of enthusiasm.” [kallsinnighet och brist på enthusiasm] P.M, Lennart Petri, March 4, 1947.

- Application for access dated October 2, 2022. See also January 3, 2023, Appeal to the Administrative Court of Appeals [Kammarrätten] of the decision by the Swedish Security Police (Säpo), Reference number 2022 -25939 – 7, dated December 8, 2022.

- January 3, 2023, appeal to the Administrative Court of Appeals regarding the decision by the Swedish Security Police, Reference number 2022 -25939 – 7, dated December 8, 2022.

- The same is true for Guy von Dardel’s lawsuit against the Soviet Union in 1984-1989. The litigation should have created intensive discussions behind the scenes, yet very few records about this issue are contained in the official Raoul Wallenberg dossier in the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Both the Eliasson Commission and the Swedish Working Group hired Swedish intelligence experts to review some of the Swedish intelligence documentation, but these reviews were far from systematic or complete.

- One such case, that of the Swedish sea captain Karl-Johan Fast, figured in the discussions between Ambassador Rolf Sohlman and his KGB contact in 1960-61. See https://susanneberger.substack.com/p/the-raoul-wallenberg-research-initiative-bff?r=1y95mt

- https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svar-pa-skriftlig-fraga/raoul-wallenberg-och-fange-nummer-7_h812893/

- https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/webb-tv/video/fragestund/fragestund_hcc120241017fs/?pos=3516&autoplay=true, from 58:36

No responses yet